Andrea

Gunder Frank, like Baran, was interested in identifying the causes of

underdevelopment, but unlike his predecessor he did not lay great emphasis on

the social classes and their control over the economic surplus (Frank 1967).

Rather, Frank argued that the crucial mechanism for extraction of the surplus

was trade and other kinds of exchange of goods and services, not only

international trade, but also exchange internally in the peripheral societies.

Frank

rejected the dualist conception according to which the underdeveloped countries

comprised two separate economies, one modern and capitalist and another

traditional and non-capitalist. On the contrary, he claimed that capitalism

permeated the whole of the periphery to such an extent that the Latin American

and other peripheral societies had become integrated parts of a one-world

capitalist system after the first penetration by metropolitan merchant capital.

This had established capitalist exchange relations and networks that linked the

poorest agricultural labourers in the periphery with the executive directors of

the large corporations in the USA.

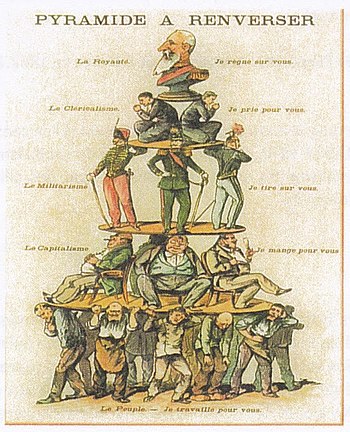

The

exchange relations and the network were described by Frank as a pyramidal

structure with metropoles and satellites. The agriculture,’ labourers and the

small farmers in the rural regions of the periphery were satellites at the

bottom. They were kinked, mainly through trade, to the landowners and local

centres of capital accumulation that is local metropoles. There is turn, were

satellites in terms of regional economic elites and centres of surplus

extraction. in this way the structure grew —through several links — until it

reached the ruling classes and world centres of capitalism in the USA.

Throughout this pyramidal structure surplus was appropriated by the centres

which, in turn, were subject to the surplus extraction activities of higher

level centres.

|

| Wikipedia Image |

According

to Frank, empirical evidence showed that the economic surplus generated in

Latin America was drained away. Instead of being used for investment in the

countries of origin, most of the surplus was transferred to the affluent

capitalist countries, especially the USA. Frank’s basic point was that the

satellites would be developed only to the extent and in the respects which were

compatible with the interests of their metropoles.

And here experience showed,

according to him, that neither the USA nor the other industrialized countries

had any interest in genuine development of the Latin American countries. Much

indicated in fact that precisely those countries and regions which had the

closest links to the industrialized countries were the proportionally least

developed. Therefore, the explanation of under development lay primarily in the

metropole — satelite relations, which not only blocked economic progress, but

also often actively underdeveloped the backward areas further (this being a

process and not a state).

Frank

derived from this the much debated conclusion that all countries in Latin

America as well as other Third World countries — would be better off if they

disassociated themselves from, or totally broke the links to, the USA and the

°thee industrialised countries. De-linking from the world market was the best

development strategy_ This presupposed the introduction of some form of socialism

in the peripheral countries, because the ruling classes, the landowners and the

comprador capitalists could not be expected to bring about such a de-linking

and thus remove the foundation for their own surplus generation.

Frank’s

conclusions, according to both contemporary and later critics, were often drawn

further than the analyses warranted. However, this did not prevent his

fundamental views and conceptions from winning wide dissemination and achieving

considerable impact upon the development debate throughout most of the 1970s.

Frank’s position in this regard came to resemble that of Rostov in the sense

that they both, for more than a decade, functioned as major reference points in

the debates on dependency and economic grow respectively. Like Rostov, whose

position was gradually superseded by more nuanced and empirically better

substantiated theories within his research tradition, Frank eventually was

replaced by more complex and differentia” attempts at explaining the

reasons for underdevelopment and its dynamics. One of the earliest attempts in

this direction came from Sarnir Amin.

Amin

was one of the first economists from the Third World who acquired a prominent

international position in the development debates, including the debates in Western

Europe and North America. Two of this academic works, in particular,

contributed to this prominence: Accumulation on a World Scale, and

unequal development.

While

Frank chiefly concerned with the conditions and relations of production. Based

on thorough historical analysis of how Europe had under developed large parts

of Africa in the colonial era, Amin worked out two idea-type societal models

with the main emphasis on the structuring of production processes. One model

described as auto-centric centre economy; the other a dependent peripheral

economy.

The

model of auto centric economy has features similar to those included in

Rostow’s description of the industrialised countries in the epoch of high mass

consumption. The auto centric reproduction structure is characterized by the

manufacturing of both means of production and goods for mass consumption,

Furthermore, the two sectors are interlinked so that they mutually support each

other’s growth. Similarly, there is a close link between industry and

agriculture. The auto centric economy is general characterised by being

self-reliant.

This does not imply self-sufficiency. On the contrary, a highly

developed capitalist economy typically engages in extensive foreign trade and

other international exchange relations. Bur the economy is auto centric in the

sense that the intra-societal linkages between the main sectors predominate and

shape the basic reproduction processes. It is the internal production relations

hat primarily determine the society’s development possibilities arid dynamics.

It

is quite a different matter with the peripheral economy. According to Amin,

this type of economy is dominated by an ‘over-developed’ export sector and a

sector that produces goods for luxury consumption. There is no capital goods

industry, and only a small sector manufacturing goods for mass consumption.

There are no development-promoting links between agriculture and industry. The

peripheral economy is not self-reliant, but heavily dependent on the world

market and the links to production and centres of capital accumulation in the

centre countries.

It

is further part of the picture of the peripheral economy that it is composed of

various modes of production. Capitalism has only penetrated limited parts of

the production processes while other parts, and quantitatively greater ones,

are structured by non-capitalist modes of production. On this point, Amen’s

conception is more in line with Baran’s mode of reasoning and hence, in

opposition to Frank’s definition of capitalism, in terms of exchange relations.

Amin endorsed the thesis that capitalist dominates the periphery within the

sphere of circulation, but he asserted at the same time that pre-capitalist

modes of production continue to exist and that they exert considerable

influence on the total structure of reproduction.

The

distorted production structure in the peripheral countries and their dependence

is a result of the dominance of the centre countries. It is the centre

countries who, by extracting resources and exploiting cheap labour, have

inflicted on the peripheral economies the ‘over-developed’ export sector. At

the same time, the centre countries have prevented the establishment of

national capital goods industries and the manufacturing of goods for mass

consumption. in these areas the rich countries continue to have a vital

interest in selling their goods in the peripheral markets.

If

the less developed countries operating under the circumstances are to initiate

a development process than can lead them in the direction of an auto centric

economy – if they are to achieve growth with at least a minimum of equity in

social and spatial terms – then they must break their asymmetrical relationship

with the centre countries. In its place they must expand regional cooperation

and internally pursue a socialist development strategy.

Amen’s basic notion

of the differences between the pure auto centric economy and the likewise

stylised peripheral economy was taken over by many dependency theorists, but

often with the addition of new dimensions and more nuances. Before considering

these elaborations we shall briefly overview Emmanuel’s – and Geoffrey Kay’s

special contributions to the dependency debate.

Discover more from Umuco Nyarwanda

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.