One of the first tasks that were undertaken by every

missionary group which entered the country was to commit to learning and

writing the vernacular language of the area in which they had opened their

mission station. The next step was to start a school and teach the people the

elements of reading and writing.

<

p style=”line-height: 150%; margin-bottom: 12.0pt; margin-left: 36.0pt; margin-right: 0cm; margin-top: 12.0pt; margin: 12pt 0cm 12pt 36pt; mso-list: l1 level2 lfo1; mso-outline-level: 2; mso-pagination: widow-orphan; text-align: justify; text-indent: -18pt;”>Missionary

education in Zambia

Missionary

Groups

Before

missionaries came to settle permanently in present-day Zambia, they had several

abortive attempts to establish mission stations. Nevertheless, they did not

tire but continued trying to penetrate the country.

Fredrick

Arnot was one of the timely great missionaries of the pioneer period. Born in

1855, Arnot was the first missionary after David Livingstone. Inspired by hearing David Livingstone speak about Africa, he decided to help David

Livingstone in his work. At 24 years Arnot came to Africa and his aim was to

establish a missionary station along the upper Zambezi River.

He

started evangelizing as he was going along the river before he could establish

a mission station, he had to seek permission king Lewanika. Though Lewanika did

not express excitement over the opening of a school due to the problems he had

in his kingdom, he did not refuse Arnot to open a school. Arnot opened his

first school in March, 1883 with an enrolment of three pupils all of whom were

boys and one untrained teacher, among the Lozi people. He also opened a mission

station under the name Christian Mission to Many Lands (CMML).

Despite

the difficulties, dangers, hardships and apathy of the African people, the

number of missionaries continued to increase. Another missionary after Fredrick

Arnot who stayed for a short time stayed in Western province. Arnot was

succeeded by Francois Coillard of the Paris Evangelical Missionary Society

(PEMS) who established his first mission station at Sesheke in 1885 and at

Sefula in 1887. Sefula remained the field headquarters for the Paris mission.

He worked among the Lozi people and his first teachers were Basuto’s who

accompanied him on his long journey from South Africa.

The

second missionary society to enter the country from the south were the

Primitive Methodists. The group opened a station at Nkala (the ruins of which

can now be seen in the Kafue Game Park) in 1893. Later on other mission stations

were stations were established on the Kafue and Zambezi rivers. From an

educational point of view, the most important station at Kafue which John Fell

built and opened was a Teacher Training Institute in 1918.

Another

group of missionaries that penetrated into Northern Rhodesia from Tanganyika

were successful and opened the first London Missionary Society (LMS) station on

the Lakeshore of Tanganyika in 1883. Later they opened up stations among the

Mambwe, Bemba and Lunda people. The most important educational centre Mbereshi

was founded in 1900. Furthermore, the missionary group decided to call in a

lady missionary to take care of the women and girls’ education. The missionary

was Mable Shaw who introduced girls’ education in 1915.

There

came another group of missionaries from the church of Scotland. The group was

led by Robert Laws. Laws built the first church of Scotland mission station on

the shores of Lake Nyasa in 1875. Twenty years later, in 1894 he opened the

famous Livingstonia Institute at Kondowe. In the same year, a mission station

was opened (1894) inside North-Eastern Rhodesia near Fife among the Namwanga

people. At Chitambo where Livingstone died, a mission station was opened in

1907 by Malcom Moffat and Dr Hubert

Wilson, a grandson of the great explorer (David Livingstone). On the other

hand, an African missionary named David Kaunda, educated at Livingstonia had begun

evangelistic work in Chinsali area and his efforts led to the establishment of

a mission station at Lubwa. Later in 1922, another mission station was opened

at Chasefu among the Tumbuka people of Lundazi district.

Later

on, came the White Fathers who opened a mission station at Kayambi in 1895.

Under the leadership of Bishop Joseph Dupont, the society expanded its

activities. Bishop Dupont was nicknamed moto-moto (great fire) because of his

dynamic leadership. After gaining a foothold among the Bemba people, the White

Fathers Succeeded in establishing a strong network of station throughout

Northern, Eastern and Luapula Provinces. White Fathers continued to stream into the envy of non-Catholic missionaries who even saw the coming in of lay brothers,

a little later White Sister too set up mission stations throughout the eastern

half of the country. The other society who were trying to match the White

Fathers in numbers were the missionaries of the Dutch Reformed Church. Their

activities were almost confined to the Eastern province. The Dutch opened their

first church in North-Eastern Rhodesia (now Zambia) in Magwero in 1899. Further, a chain of strategically situated stations covered the Fort Jameson (Chipata)

and Petauke districts.

Other

Pioneer Mission Groups 1901-14

The

Catholic missionaries came in large numbers as compared to the others. In the

south of the country came the Jesuit Fathers. The Jesuits arrived at Chikuni

mission under the leadership of Father Joseph Moreau in Monze district and

established a mission station in 1905 among the Tonga people. Another mission

station was also opened at Kasisi east of Lusaka by Father Jules Torrend in

1906. From these stations other centres were opened largely in the Southern and

Central provinces of Zambia.

In the

same year 1905, four days before the Jesuits arrived at Chikuni, an American

from Indiana, William Anderson a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church

(SDA) church also arrived. He began building a mission station at Rusangu in

Monze district. Subsequent expansion of the SDA activities led to the

establishment of widely scattered station near Ndola, kawambwa, Kalabo, Chipata

and Senanga. Rusangu remained the most important centre because of the

education activities.

Another

group of missionaries who entered Northern Rhodesia as an extension of their

work are the Brethren in Christ Church in 1906. Two American ladies, sisters

Annah Davidson and Addah Engle arrived at Macha in Choma district of Southern

Province. Due to lack of money and personnel, the Brethren in Christ only

opened two other station and could not go beyond that. Bishop Hine of the UMCA

opened the first Anglican station at Mapanza in Choma district among the Tonga

people in 1911. Another station was opened in Msoro area among the Kunda people

in Chipata by an African Priest. However, the UMCA did not give much support to

the mission stations as they had done in Uganda. They only gave support to

Mapanza because of its significance to educational work which it wanted to

develop.

The

other society which was the last to enter the country before the 1914-18 war

was the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary Society. They opened a station at

Chipembi in 1913 under the leadership of Henry Loveness and Douglas Gray. Other

stations were opened at Broken Hill, Lusaka and at Keembe in the western part

of Lenje reserve. Chipembi was developed as the society’s educational

headquarters and led the way in agricultural work and girls’ education.

Chipembi girls’ school was opened in 1927.

In

1926, Salvation Army came and established a mission station at Chikankata, they

also had a hospital within the vicinity. A further reinforcement of Catholics

arrived in 1913. These were the Capuchin Fathers who opened mission stations in

Lukulu, Maramba and Mongu which became important educational centre. The

Franciscan Fathers starting from Ndola in 1931, opened missions on the

Copperbelt mostly important was Ibenga Girls Secondary School as an educational

centre. Another small group was the Pilgrim Holiness Church which began its

operation in 1933 in Southern province.

To sum

up on the arrival of missionaries groups, a mention must be made of two further

bodies, the Church bodies such as United Missions on the Copperbelt. This was

formed in 1936 when representatives from London Missionary Society, the Church

of Scotland, the Universities Missions to Central Africa, the Methodists and

South African Baptist put their resources together in support of their work.

This was because of the educational problems they faced. The Franciscan and

Dutch Reformed Church also provided staff for the venture.

Closely associated with the United Missions on the

Copperbelt was the United Society for Christian Literature, it had a small

thatched hut in Mindolo, Kitwe. It was the headquarters for educational

materials in Northern Rhodesia charged with the responsibility to provide

Christian literature on the Copperbelt. It was opened in 1936. Society rapidly became the main source of supply for school textbooks and also played

an important part in stimulating the production of local books.

Early

western schools in Zambia.

Although

the early missionaries were separated by distance and in most cases without

contact between them, there was closeness among them in their assessment of the

problems they encountered in their missionary work. In view of trying to

capture as many African converts as possible, they devised the strategies and

tactics of their evangelistic campaigns. The African culture according to

missionaries was doomed to spiritual damnation as it was immoral, lazy,

drunken, steeped in superstition and witchcraft. According to them the whole

culture was rotten and needed to be replaced root and branch.

In view

of this, the Primitive Brethren Missionary Frederick Arnot opened the first

school, the Barotse National School in 1906, the aim was to educate, evangelize

nurture Christian leadership. In the case of PEMS Francois Coillard opened

about five schools which were operating in villages. Coillard’s aim of

education was to make his students literate and provide higher education for

bright pupil’s. For instance, he sent five young men to Basuto land from Sefula

to a missionary training school.

The

London Missionary Society under the leadership of Bernard Turner trained

hundreds of African youths in building, carpentry, metal work and other crafts.

On the same station, Mable Shaw pioneered the development of girl’s education

in the country teaching various aspects of homecraft at Mbereshi.

Father

Joseph Moreau, the Jesuit father at Chikuni taught people how to improve the

productivity of their gardens and cattle.

In

conclusion, it must be mentioned that the largest societies had the capacity to

expand their education most rapidly than small societies. Of the two thousand

or so schools operating in 1925, more than half were under the control of White

Fathers (554), Dutch Reformed Church (448), Church of Scotland (308), London

Missionary Society (280) and the management of the remaining 400 schools was

divided among the eleven smaller groups. The extraordinary rapid rate of

expansion was due to superior resources i.e. personnel and finances.

It should be emphasized that the main motive for

educating the people by the missionaries was to make people understand the

gospel of Jesus and be able to read the Bible. The Africans were also to spread

the gospel in places where missionaries were unable to reach hence the white

missionaries needed to train them to preach and read.

The

General Missionary Conference of 1914

The

July 1914 Missionary conference was the first to be held among all the others.

This conference was held in Livingstone in the Coillard Memorial Hall. It

lasted four days and was held with a view to overcoming some challenges that

were being faced in education by the different missionary societies. Snelson

1974 advances that the Primitive Methodists were the initiators of the

missionary conferences which were to exert considerable influence in the

country for a period of not less than thirty years. Originally, the Primitive

Methodists after deciding to translate the New Testament into the Ila language

called for representatives from other missionary societies using the language

to assist them revise the manuscript. Being impressed with this success at an

attempt at co-operation, the missionary societies entertained the thought of

having meetings of a similar nature to discuss problems that were common to

them all. Among the missionary societies represented were:

•

The

Paris Evangelical Mission (PEM)

•

The

Brethren in Christ (BIC)

•

The

Universities Mission to Central Africa (UMCA) and

•

The

Wesleyan Methodist (WM)

Working

together, the representatives from the above-mentioned missionary groups with

those from the PM unanimously elected a President from amongst themselves whose

name Rev Edwin Smith. The July 1914 Missionary conference like any other

conference was held with four objectives. The objectives are listed below

though not in any order of importance:

·

To

ensure brotherly feeling and provide co-operation among the various missionary

·

To

toil for a speedy and effective evangelization of the races in North-Western

Rhodesia

·

To

enlighten public opinion on Christian Mission and

·

To

guard the interest of the native races.

As

indicated earlier, the conference lasted four days and apart from simply

considering ways to meet the set objectives, issues of other educational

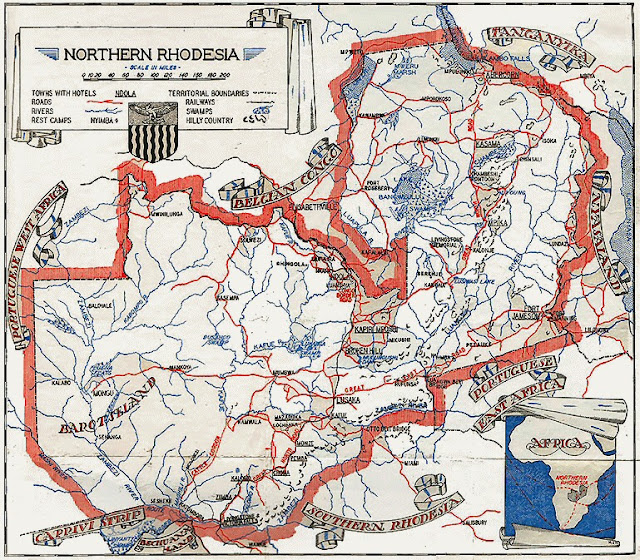

problems experienced by the missionaries crept in. When you refer to the map of

Zambia given in this module you will discover that many schools were set up and

by various missionary societies. This implies that before the conferences, each

missionary society drew up its own curriculum and school actives were also

carried out differently from one group to the other.

The

general missionary conference of 1919.

The

second General Missionary Conference was held from 18-22nd July, in

1919. It was also held in Livingstone under the chairmanship of Rev. Adolphe

Jalla of the PEMS. His secretary at the same conference was Rev. John Fell of

the PMMS. This conference was held as a result of the Native Schools

Proclamation of 1918. The main purpose of the conference was to suggest

amendments to the proclamation. The attitude and spirit of intolerance detected

in the proclamation were greatly condemned by the conference. The major

amendments made at the conference included the following:

•

unmarried

teachers or those that were married but not accompanied to the new stations by

their wives be not placed in villages where no European missionary is resident

for a period exceeding three months without the express permission of the

magistrate.

•

that

prayer houses be excluded from the definition of schools

In

addition to the above, some resolutions concerning education were also passed.

The first being that the government should give grants to aid the educational

work of the missions. At this same conference a school code drawn up by Fell

was also accepted. At the end of the conference, the delegates agreed to extend

invitations to missionary societies based in North-Eastern Rhodesia.

Having

examined the reactions of the missionaries to the 1918 Native Schools

Proclamation, write brief notes on the response of the government.

The

General Missionary Conference of 1922

This

was the third General missionary conference. It was held in Kafue from 17th

to 23rd July in 1922.The leadership of this conference was elected

as follows:

President:

Bishop R D McMinn from the Livingstonia mission

Secretary:

Rev John Fell

The

delegates from the eleven missionary societies which were represented discussed

a good number of issues which included native reserves, objectionable native

marriage customs, spheres of influence, native taxation and the need for native

ministry.

The

issues above were discussed alongside the three papers presented by Coxhead

JCC, Dr Loram D T, and Latham G C. The paper for Coxhead, who was the secretary

for Native Affairs talked about the need to appoint an expert in agriculture

who would advise the mission s on agriculture education. In his presentation

Coxhead added that the Administration was ready to pay one third of the expert’s

salary provided the missions could pay the balance. In the second paper Loram,

an eminent educationist from Natal advocated that primary education be retained

by the missionaries and that though this would be the case, there would still

be need for the government to give financial support to the missionaries.

Secondary education, however, would be run by the state. Snelson (1974) further

presents that in the same paper it was suggested that the administration should

consider setting up a central institution in Northern Rhodesia on the lines of

Fort Hare in South Africa. In addition to academic work, training in

agriculture and courses for chiefs would also be provided. Chiefs needed to

undergo some training because they obstructed development in their areas. Dr

Loram concluded his paper by recommending that an advisory board be established

to foster close co-operation between the missionaries and the administration.

The third last paper was presented by Latham GC. He was a former district

officer. At the time of the conference, he had been appointed to the post of

part-time inspector of schools for the country. Latham emphasized the need for

co-ordination of effort among the agencies engaged in education. He also added

the following:

•

That

in order for the co-ordination of the effort to be successful, there was need

for the missionaries to agree amongst themselves about their respective sphere

of influence so that they did not step into the area of the others.

•

That

the missionaries put their denominational differences aside and that mission in

North Eastern Rhodesia put their resources together to provide a first class

normal school for teacher training that would match schools at Sefula in the

west and Kafue in the central area.

•

That

the curriculum be carefully balanced between the religious, academic and

industrial elements.

•

That

a modest scale of government grants for mission schools, where in addition to

literary education, industrial training of at least two hours a day was given.

The

General Missionary Conference of 1924

This

was the last conference. It was held in June, 1924 in Kafue. According to

Snelson (1974), the main purpose of this conference was for the missionary

members to meet the Phelps-Stokes commission, and to make strong

recommendations to the new government on an educational policy for the country.

This conference was characterised by excitement and optimism and there were

addresses by Jones, Aggrey, Vischer, Fell and many others. By the time of the

conference, the BSA Company had relinquished its administrative

responsibilities and all including the missionary societies were happy with

that development. The missionaries were optimistic that the new government

would strive to correct things and assist them come up with a worthwhile educational

system. From the drafted resolutions presented at the conference for its

consideration by Jones and Fell, points were taken and combined and a lengthy

resolution arrived at.

Snelson

(1974) quotes from ‘Proceedings of the General Missionary Conference of

Northern Rhodesia,1925’ that in their resolution, the missionaries recognised

that though secular education was the duty of the state, they desired to share

in the provision of the same to the natives. The resolution further presented

that the missionaries believed that co-operation between them and the

government would be in the best interest of this education. The resolution

stated that the basic principles for all educational work would be that both

Primary and Secondary education would be undertaken in mission schools with aid

from the state. Higher education was to be undertaken in government schools

with mission aid.

The

conference also recommended that in order for the principles to be carried out

there was a need to appoint a Director of Native Education and a board of Advice

on which missions would be represented. The other recommendations put forward

were as follows:

•

That

financial aid be granted to Central mission schools

•

That

financial aid is given so as to establish a cadre of visiting teachers for the

improvement of village schools.

•

That

financial assistance be given to Primary schools

•

That

government High schools with denominational hostels be established and

•

That

the apex of the educational system be a central institution of colonial

dimensions which would offer higher education to those who could profit from

it.

If we

compare what was discussed in the earlier conferences to what was discussed in

this conference, we can conclude that there was a repetition of some demands

and just an addition of a few more.

The Phelps-Stokes commission.

The Phelps strokes commission was set up in New York

under the will of Miss Caroline Phelps Stokes to further the education of

Negroes in Africa and the United States, (Snelson,1994). The first commission

that was set up visited the south, west and equatorial Africa under the leadership

of Dr Jones who later wrote a report about the same visit. This report raised a

great deal of interest and as such another commission was set up which would

this time visit East and Central Africa. Among the members of the commission

were: Dr Jones Aggrey,a distinguished educationist from Gold Coast( presently

Ghana); Dr J.H Dillard from the USA who was the President of the Jeans fund, Dr

H.L Shantz, agriculturalist and Botanist from the USA; Rev Garfield Williams,

education secretary of the church missionary society; Major Hanns Vischer,

secretary of the Colonial office advisory committee on native education in

tropical Africa, C.T Loram of South Africa and James Dougall from Scotland. The

chairman of the commission was Dr Thomas Jesse Jones.

The

Phelps Stokes Commission was charged with a threefold task:

1. To investigate the education needs of

the people in the light of their religious, social, hygienic and economic

conditions

2. To ascertain the extent to which

their needs were being met and

3. To assist in the formulation of plans

to meet the educational needs of the native races.

Between

January and July 1924, members of the commission visited French Somali land,

Abyssinia,

Kenya, Uganda, Tanganyika, Zanzibar, Portuguese East Africa, Nyasaland,

Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and the Union of South Africa. The

commission divided itself so as to cover all the countries indicated above. The

party that visited Northern Rhodesia from 8th to 13th was

made up of Dr Jones, Aggrey, Vischer and Dougall. This group spent most of its

time at the General missionary conference held at Kafue in order to meet the

missionaries.

The

following were the recommendations of the commission (note that only the

recommendations that concerned Northern Rhodesia are discussed below):

1. The government to appoint a Director

of native education whose task would be to coordinate and unify the educational

activities of the missionary societies.

2. An advisory committee on education

should be appointed with representatives of government, the missions and the

settlers.

3. Provision should be made for the

representation of the native opinion.

4. Government should subsidize the

educational work of the missions (Grants-in-aid to missions).

5. Priority should be given to the

establishment of teacher training institutions.

6. There should be aid for maintenance

of European missionaries to supervise the educational work of their mission

stations and out schools.

Adopted from Snelson (1974)

The British South Africa Company and

Education

When was the first time you heard about the British

South Africa Company (BSA Company)? Mention some of the major achievements of

the BSA Company.

Check if you included any of the following:

·

The company contributed largely to ending slave trade

·

Helped to end most of the tribal wars (inter-tribal

war)

·

Helped to bring about law and order in Northern Rhodesia

as a result of establishing an administrative system

The BSA Company gained control over North-Western and

North -Eastern Rhodesia in the 1890s.Its task was to administer the two

territories mentioned above which were eventually combined in 1911 and later

came to be known as Northern Rhodesia. This, the company did on behalf of the

British government until 31st March, 1924.

“Although the company achieved considerable success in

ending the slave trade, putting a stop to inter-tribal wars, creating an administrative

system it’s record in regard to the African education was one of consistent

neglect. Development schemes which were not strictly essential- and education

for the Africans did not come within the definition- could not be countenanced.

For three decades, these somnolent years as Hall dubbed them, the company

consistently refused to give financial assistance to missionary educational

enterprise in the country and failed lamentably and shamefully to implement the

explicit promises regarding education which had been made in the treaties with

Lewanika, paramount chief of the Lozi and with other chiefs when the

concessions were granted which established the company’s authority” (Snelson 1974: 121)

The BSA company was not really committed to the

development and advancement of native education in Northern Rhodesia. In the

case of Lewanika treaties were signed in 1890, 1898 and 1900 in which he

(Lewanika) was assured that schools would be provided for his people. In

addition, there was a promise to aid and assist in the education and

civilization of the natives of his land. The provision of the aid and

assistance would be facilitated by the establishment, maintenance and endowment

of schools and industries. However, the BSA company did not live up to its promise.

Carmody, 2004 further adds that for the thirty-four

years that the BSA company administered the territory, it established only one

school. This being the Barotse National School set up in 1906 at Kanyoyo. This

was despite it (BSA co) collecting large sums of money in taxes from the local

people. Most of the teachers that were tasked to teach in the few available

schools were poorly educated, in addition to not being trained and being very

poorly paid. All this bordered on the fact that the BSA company refused to

support education though it was eager to control the education system through

its 1918 Native Schools Proclamation.

(Adapted from Snelson1974)

The British Colonial Government and

Education

A year

after taking office from the BSA company, Sir Herbert Stanley (the governor in

the colonial office) created a sub-department of Native Education. This

sub-department was under the Department of Native Affairs. Geoffrey Chitty

Latham was immediately appointed as Director. Snelson 1974 describes Latham as ‘one

among the most capable men in government service who had held different posts

from the time he joined the administrative service of the company in 1910.

Latham

was faced with a mammoth task of ensuring to create a coherent and

comprehensive system on education that would suit the needs of the country and

its people. At the time of his appointment, there were fifteen missionary

stations and almost 2000 schools in which were enrolled almost 100 000

children. The teachers who taught these children had very humble professional

training and the syllabus followed was not in any order while the equipment and

learning materials used were inadequate. As such the education system that

Latham had to come up with was to be one that would cater for both the large underdeveloped

rural areas and the growing townships in the line of rail. Among the people who

were to support Latham in his work were:

•

William

Mhone (an African clerk)

•

John

Keith (a native commissioner)

•

Rev

J R Fell

•

Hodgson

F • Cottrell J A

•

Miller

D S

•

Opper

C J

The

people listed above joined Latham between 1928 and 1930. As such Latham worked

tirelessly by himself in the first years and laid the foundations of the

Educational Administrative System in Northern Rhodesia. The system was to last

until independence. He (Latham) retired in 1831 and is referred to in some

cases as the father of African education in Northern Rhodesia. During his six-year

tenure in office, Latham contributed greatly to many issues in education. He

built up a department that was able to stand on its own by 1930. That is to

say, the department stood independent of the Department of Native Affairs. The

Department was planted on the site of the Jeanes school at Mazabuka. The other

of Latham’s achievements included the following:

•

He

encouraged efficiency in the work of the missions and evolved a system of

grants-in-aid to them. He also emphasized the need for quality in education as

opposed to quantity, which was desired by most missions.

•

He

attached a lot of importance to teacher training and constantly remained the

missionaries on the need to have well-trained teachers as they were a basis on

which a good school could be run.

•

With

the involvement of John Fell and the advisory board, Latham secured the

acceptance of common syllabuses which were to be used at all educational levels

throughout the country.

•

He

expressed displeasure at education that was purely academic. He indicated that

such a type of education was unsuitable for the needs of the people. Instead,

he fought to promote industrial and agricultural training which would with time

raise the standard of living all throughout the country.

•

He assisted in the development of girl’s

boarding schools in every province. With a belief that through the provision of

such, girls would be helped to have equal access to education and be prepared

for domestic and maternal duties.

• He managed to convince mining

companies in the developing urban areas of the importance of setting up schools

in their townships.

5.4.1

Education during the

War period 1939-1945.

During

the 1930s Educational development took place on a very modest scale. The

1939-1945 war however transformed the Northern Rhodesia economy and produced

the money that was required for the educational system.

There

was a lot of demand for raw materials by the allied powers for war. Output from

copper mines soared. Production during the six years of the war totalled almost

1,500 000 tons (copper prices which had fallen to £ 25.6 in 1932 rose to £ 66.1

per ton in 1941-46.

At

Broken hill mine production of Lead, Zinc and Vanadium were increased and the

production of these commodities also rose. The greatest benefactors from this

boom in the country’s mining industry were the shareholders in the BSA CO which

had appropriated the mineral rights of North-Western Rhodesia half a century

earlier.

Nevertheless,

the government also shared in the general prosperity through its receipt from

taxation. For the first time in the country’s history substantial sums were

available for spending on the development of social services. During the period

1939- 1945 government expenditure on

African education rose rapidly as follows;

1939 –

£ 42 286

1940- £ 55 182

1941 – £ 69 453

1942 – £ 88 483

1943 – £ 99 405

1944 – £ 123 200

1945 – £ 149 450

Adapted

from Snelson (1974, p. 236)

5.4.2

Education during the

Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

The federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland is also known

as the Central African Federation. It was established on 23 October, 1953 at

the instigation of white settlers and against strong opposition from Africans

who saw it as marginalizing them and an attempt by white settlers to entrench

power in the territory.

Fearing that the two Rhodesians might link up with

South Africa, the British government capitulated to the wishes of white

settlers.

Northern Rhodesia’s copper industry was the prize the

federal government in Salisbury wished to exploit. During the federal period, almost £ 100 000 was

transferred in tax from Northern Rhodesia to Salisbury

mostly for developments in Southern Rhodesia.

During the federal period, the mining industry was the

only part of Northern Rhodesia’s economy

that developed. Education during this period was racially segregated. The

Northern Rhodesia government was responsible for African education while the

federal government was responsible for the education of all other races and for

higher education.

There was an unbalanced allocation of resources with the

larger share going to educational developments for non-Africans and a

relatively small share going to the Northern Rhodesia government for African

education. This was in spite of the fact that copper revenues from the North

financed most of the educational developments for all races.

In Northern Rhodesia,

more secondary schools were opened especially after 1956. Trade schools

developed and some technical education was provided at Hodgson Institute in

Lusaka. Tentatively early moves in 1952-53 towards the establishment of a

university in Lusaka frightened the federal authority in speeding up the

development of the university college of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. This was

opened in Salisbury in March 1957.

Discover more from Umuco Nyarwanda

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.